The Greeks had a word, hubris, that gets thrown about a lot. I have the impression that it means something like “self-confidence.” Right? Self-confidence is great stuff! Empowering! There are no challenges that human ingenuity cannot overcome: social conflicts, climate change, plagues and pandemics. We’ll just power through it all like a tank through soap bubbles.

I must admit that not every science fiction author adopts this buoyant stance. Some of them have taken a contrary point of view, in fact, positing that there are some circumstances that will defeat humans, no matter how smart and persevering they are. Circumstances like alien worlds that cannot be terraformed into human-friendly resort planets. Here are five worlds that steadfastly resist meddling…

C.J. Cherryh’s Cyteen, capital of an interstellar great power (Union) and setting for the eponymous novel (published in 1988), is, like the worlds selected for colonization in Brian Stableford’s series, remarkably Earth-like. The air is to a first approximation breathable, the climate is tolerable, there is neither too much water nor too little. Compared to planets like Mars or Venus, it’s a paradise! There is just one minor catch: Cyteen’s biochemistry developed along different lines than did Earth’s. The planet is a “silicate-polluted hell,” lethal to unprotected terrestrial lifeforms. Without high technology to filter the air, Cyteen would be uninhabitable by humans.

Lois McMaster Bujold’s Vorkosigan universe demonstrates that worlds can be in a general sense “Earth-like” while at the same time lacking many essential factors required for a survivable shirt-sleeve environment. Marginal worlds outnumber garden worlds by a considerable margin. Thanks to a desirable location, Komarr (the planet which lends its name to the 1998 novel) attracted investors and colonists, who spent centuries terraforming it. They managed to transform it from an icebox world that would kill an unprotected human in minutes to a (marginally) warmer world on which unprotected humans can survive for a few more minutes. Komarrans are utterly dependent on their advanced infrastructure and life support systems, which no doubt is a huge advantage when it comes to getting maintenance budgets passed.

Donald Kingsbury’s Courtship Rite (1982) focuses on the human cultures that have developed on the arid planet Geta. Geta is inhospitable but not immediately deadly. Humans can breath the air and survive the usual range of temperatures. But native Getan lifeforms are for the most part inedible or even poisonous. A few can be eaten after processing. Human life depends on the eight sacred plants (familiar Earth crops like wheat, soybeans, and potatoes) and on bees. The only meat is human meat. Geta has forced its human population to adapt in ways that may seem shocking to the reader.

In Poul Anderson’s short story “Epilogue” (1962), the good ship Traveler set out from an Earth on the brink of war to settle Tau Ceti II. The Traveler’s poorly understood field drive delivered it to an Earth eons in the future. The Earth of the future is nearly hot enough to boil water. There is no free oxygen; the atmosphere is composed of nitrogen oxides, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide, and steam. There is no evidence that organic life survived the war. However, humanity’s replicating machines did survive. In fact, they thrived, shaped by natural selection just as organic life once was. By the time the would-be colonists return to Earth, it has new masters, curious entities alongside whom humans are very unlikely to thrive.

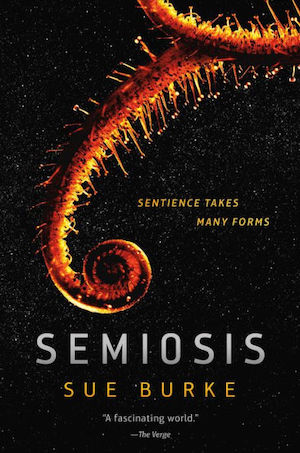

Sue Burke’s Semiosis (2018) begins promisingly enough; a community of idealists sets out to found a new society far from Earth’s violence. Their problems only begin when they wake to find themselves orbiting the wrong world, which they optimistically name Pax. Older than Earth, Pax is home to a rich, diverse biosphere. It’s a world that offers the naive settlers a bewildering range of ways to die. Survival depends on convincing the dominant lifeforms that humans are worth the bother of preserving. That, in turn, depends on humans recognizing those dominant lifeforms for what they are.

No doubt you have your own favourite hellish deathworlds (that’s a catchy title; someone should use it), examples that you are even now leaping to your keyboards to bring to my attention. The comment section is, as ever, below.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is currently a finalist for the 2020 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.

Maybe these are too obvious but:

Arrakis

Eddore

Salusa Secundus

Palain VII

Grayson from David Weber’s Honorverse is a perfectly lovely planet except for all the heavy metals.I don’t think it’s in the die instantly category but it’ll kill in you in unpleasant ways eventually.

There’s a Poul Anderson short in which colonists discover over the course of generations that a planet each of whose parameters were within acceptable limits taken individually was just a bit too uninhabitable in the long run when all the off notes were taken in aggregate.

(once they conned their way back to Earth, they were comparative supermen, because science fiction)

@1: Hey, Palain is a garden planet! just ask Nadreck!

The planet Eden in ST-TOS. Yeah, brother!

Yeah, well. The space hippies should have done more basic research before chowing down on local life forms.

@@.-@ I am certain that when I ask Nadreck he will tell me that he is a person of limited mental power and any opinions he has about his planet should be taken in that context…

The Steerswoman series by Rosemary Kirstein. It’s a science-fiction mystery, so I’m reluctant to explain details. I think it was about book 3 that it was revealed in detail how lethal is much of the world, and that it’s a Clew.

I’d recommend the series enthusiastically, except that she’s like halfway through & her publication rate is glacial. The existing books are good enough that it hasn’t bothered me too much, but Your Mileage May Vary.

Mesklin from Mission of Gravity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deathworld

Perhaps disqualified on account of being insufficiently fictional, but Venus leaps to mind. Surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead, clouds of sulfuric gas in the atmosphere, and pressures you have to go almost a kilometer beneath the ocean to find on Earth.

I’d be morbidly curious to see some experts weigh in on exactly what an unprotected human transported to Venus’s surface would die of first, but unless you have spectacular timing, you probably won’t last long enough to worry about Global Resurfacing Events, or what causes the giant weblike structures called Arachnoids.

(I mean, some form of geological process, presumably, but when science hands you phenomenon named Arachnoids…)

Oddly, while being a total hellworld at the surface, Venus does have a comparatively hospitable region 50 km above the surface. No O2 and too much sulfuric acid but the temperature is OK. You’d definitely last long enough to scream a bit.

Huh. Now I want fiction about Venusian blimp cities plying the skies. I bet someone’s written some! To the search engines!

This is set on Venus. Showed up in my inbox yesterday.

@MRush I second Deathworld! Definitely a pulpy book but it’s enjoyable if you also liked the Stainless Steel Rat series.

What??? Nobody has yet mentioned Trenco?

My first thought was Mesklin, and then Deathworld, but you guys beat me to the punch! The Incredible Shrinking Man movie taught me that from some perspectives, our own planet can be pretty scary.

Almost all of Earth is inhospitable to human life but we don’t notice because we generally stick to the bits that aren’t e.g. under the sea or between the crust and mantle…

@17 @18 Earth is terrifying and filled with monsters, ask any bird or mouse…

@16 You are correct. It must have been the effect of mixing the thionite with the bentlam…

My first thought was not a literary world, but the prison moon from Chronicles of Riddick—Crematoria.

Oddly, when people don’t buy a series until it’s complete, the series often is never finished. Go figure.

Regardless, Steerswoman is highly recommended.

Alan Dean Foster’s Midworld.

Cordwainer Smith’s Shayol was pretty nasty.

@16 and @20 I was thinking of Trenco too, although I was blanking on its name.

Not technically an inhospitable planet, but I’ve got to go with one of my all-time favorite hard sci-fi books: Dragon’s Egg by Robert L. Forward and its story of intelligent life evolving on a neutron star.

Hal Clement’s universes were very lean on Earth-like worlds. Even the ones that at first glance seemed Earth-like would like as not turn out to have seasons where the oceans boiled.

In Greek plays, hubris meant overweening pride,the kind that leads to self-destruction. Think of those movies where a leader gets everyone killed rather than admit he was wrong and that they need to retreat or get help. In real life contexts, the Greeks used it to refer to violating norms of behavior, especially violent crimes, like assault and battery and sexual crimes.

It needed to be said. Hubris is how hell worlds get people who think they can handle them.

I’d offer Neal Asher’s Spatterjay as well – definitely eat and/or be eaten!

Some of the human-settled worlds in Larry Niven’s Known Space universe might fit this: Plateau (aka Mount Lookitthat) with one piece of crust at a high enough altitude, and hence thin enough air, for human life. Jinx isn’t too bad, except for the high gravity, as long as people stay within the appropriate latitudes. Meanwhile, the very alien Outsiders stay far from any sun, trading information, including technology.

Came here to say Niven’s Known Space universe is full of enticing death traps, but I see I’ve been pipped to the post!

Harry Harrison’s Deathworld planet Pyrrus has got to be a contender, surely?

I’m also going to go for whatever-the-planet-was-named in Robert Charles Wilson’s Bios (where it turns out that terrestrial life is basically incompatible with the dominant type of biochemistry found everywhere else in the observable universe and just breathing the air will rapidly kill you due to anaphylactic shock) …

Earth itself becomes thoroughly inhospitable in the future. Documented in, among others:

The Time Machine (H.G. Wells)

“Impossible Planet” (Philip K. Dick)

Planets humans can attempt to survive on – Finisterre Kesrith, Kutath, Staurn. Worlorn,

Planets humans wouldn’t attempt to survive on – Satan, Mirkheim

rpresser @32: Earth also becomes inhospitable in Hal Clement’s The Nitrogen Fix and Half Life.

Some of the classic “jungle Venus” stories come to mind, such as Weinbaum’s “Parasite Planet”.

Two of five for me. _Komarr_ (a truly excellent book published by Baen – I am astonished that James listed it) and _Cyteen_.

Deadly to most life-forms, but has some hardy native life: Earth. The atmosphere has free oxygen, if you can believe it!

There are couple of inhospitable worlds in James Blish’s And All The Stars A Stage. One I remember had insects with metallic chitin that achieved very high velocity from magnetic fields.

The world of West of January, by Dave Duncan, comes to mind. The world is almost tidally locked, so it’s “day” is 200 yrs long. People and life live near the terminator line, and slowly migrate with it.

Isis, the planet in Robert Charles Wilson’s Bios.

Plus I would think Shayol, in Cordwainer Smith’s “A Planet Named Shayol”.

Also, in a way, Earth in James Blish’s great story “Watershed” (the last story in The Seedling Stars.)

Hades, AKA Hell, in David Weber’s Honor Harrington series. It’s lush, lovely, and gorgeous, and there doesn’t seem to be anything in the jungles that cover the planet that ‘s big enough to harm a human.

But you can’t eat any of it.

The evil empire that controls Hades uses it as a P.O.W. camp. All they have to do is dump some prisoners at a designated spot with some basic supplies and make them build their own camp. Deliveries of fresh food (sans anything that could be used to preserve it in the prevailing humid conditions) arrive from the well-guarded Terraformed area. If the prisoners act up, the deliveries stop…

The various worlds in Scalzi’s Interdependency, which rapidly become uninhabitable when interstellar space flight stops working.

Alan Dean Foster has several marginally inhabitable worlds. Someone else mentioned Midworld. There’s also Tran-Ky-Ky, an ice world, and Prism, a world of silicon based life forms that humans are spectacularly unable to cope with. Alas pin has numerous interesting ways to die .

That no one has mentioned Catachan from Warhammer 40,000 is a grievous heresy that shall be duly reported to the Holy Ordos of the Inquisition forthwith. The Emperor protects!

Seriously, even in a setting filled to the brim with Death Worlds, Catachan takes the cake. The entire planet is shrouded in dense jungles hostile to human life; everything is carnivorous, plants included, and their growth rate is so absurd that every settlement on the planet faces a constant struggle to keep from being reclaimed by the jungle. The local fauna is likewise exceptionally dangerous. Happen to stumble upon a Catachan Barking Toad and decide to boop its snoot? It’ll respond by exploding into a cloud of nerve gas a full kilometre in radius (yes, its defense mechanism is not running or camouflage or intimidating spikes, but suicide bombing). And that’s one of the planet’s prey species; full-fledged predators like the Catachan Devil (a centipede monster the size of a freight train) are plentiful. Then you pencil in the numerous diseases, the presence of Feral Orks, the high gravity and the recurring hints within the lore that the planet might be both sentient and actively trying to exterminate the humans living on it, and you quickly realize why living into adulthood is considered a noteworthy accomplishment on this planet. Indeed, the Catachan Jungle Fighter regiments raised for the Imperial Guard (basically Rambo cosplayers) are so renowned for their toughness simply because, after enduring all that, there’s very little the galaxy can throw at them that phases them.

Carcosa.

It’s always a pleasure to read your pieces, and this time was no exception – very good, knowledgeable choices. I’m piping up just for a small detail.

There may be a glitch in the Poul Anderson book title. Seems to me it is Explorations, not Tales of the Flying Mountains – the latter’s brief “Epilogue” after the last tale is really the traditional closing scene, not a story.

Cf. http://poulandersonappreciation.blogspot.com/2013/08/epilogue.html and https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2952999-explorations

I think I mentioned this recently, but I can’t remember where.

There’s been a sort of long-running round robin thing on Tumblr for a while called “Earth Is Space Australia.” We come from a truly inhospitable planet; we just don’t know it. Ours is the only planet to have given rise to intelligent life while also having such active plate tectonics, such extreme climate banding, so many extreme weather events, so many dangerous wild animals, and/or so many poisonous plants. It cross-pollinates with another round robin called “Humans Are Space Orcs,” which is about human going to space and discovering that…well…we’re the Orks. Or the Klingons. Or an entire species of Doc Browns. Or the weird eldritch beings with otherworldly senses.

In one of Hal Clement’s books, we were the only spacefaring species from a world orbiting a star as massive and bright as the Sun, and the only one from a world so hot pure water was liquid.

So glad to see Alan Dean Foster’s Prism called ou

@45: Yeah, the human race is awesome like that. Glory to mankind!

@24 and@39 IRC survival on Shayol is to be expected, if not inevitable. Indeed your life is liable to be enhanced with additional legs, noses, kidneys and such.

Don’t forget Brian Aldiss’ Helliconia, with its extreme seasonal variations and helpful macroscopic and microscopic native lifeforms.

Earth itself, either through our own endeavors or from outside manipulation.

Two instances:

(1) David Gerrold’s Chtorr books. The invading lifeforms are busily “chtorraforming” parts of our planet to make it suitable for colonization.

(2) Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl, which shows our not entirely successful adaptations to an “if this goes on” situation of ongoing ecological collapse and change.

C. S. Friedman’s Erna is so tectonically active that characters know something is really wrong with an area that hasn’t had an earthquake in a century. Volcanoes and tsunamis are also a problem.

But, that’s a minor issue and one the colonists could deal with. The real problem is that there is a force on this world shaped by beliefs, including unconscious beliefs. This is a world where a child’s fear of the dark can literally create the creatures that killed his mother. The world is full of sadistic monsters with new ones being born all the time.

Perhaps even more disturbing, the colonists traveled in suspended animation for thousands of years before the computerized ship decided this planet was acceptable. All of the others it passed were worse.

N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy – inhospitable? Worse than that – the Earth literally hates humans.

A planet called Shayol. By Cordwainer Smith. One of his best tales.

A prison planet like no other.

Joanna Russ had a couple of planets just perfect for colonization!

@29 beat me to Neal Asher’s Spatterjay, and a few people have mentioned Cordwainer Smith’s Shayol, which pleases me, but I would add Fool’s Hope from John Shirley’s exceptionally cruel (to his protagonists) A Splendid Chaos. Really, more people should read it. It is a brilliantly nasty piece of work.

@51 Great book, The Windup Girl. Best depiction ever in SF of what might happen with genetic manipulation of crops, if unchecked. Especially Monsanto/Bayer and the rest of the companies who want to you to eat patented crops get away with it.

Not sure if it fits the theme of the article, though, although living in such a future Earth would be difficult. But living on Earth in the next century might probably be difficult, indeed.

As far as inhospitable future earths, there’s always William Hope Hodgson’s (almost unreadable) Night Land, where the sun has gone out, the last humans are crammed into an immense metal pyramid, and unspeakable things roam the darkness outside.

@0: In the vorkosiverse, Beta is IIRC even worse than Komarr; possibly that’s outside your parameters, as it’s not clear they’re even trying to terraform it.

The unnamed “phyto planet” of Richard McKenna’s “Hunter Come Home” ends with an interesting twist on the deathworld idea. (The story came out 3 years after Deathworld, but I don’t know whether McKenna knew Harrison’s work.) McKenna produced one of the all-time greatest opening lines (“You can’t just plain die. You got to do it by the book.”), but died just as he was getting real recognition; along with Kornbluth and Kuttner, one of the great premature losses of SF.

Avida, from Colin Kapp’s The Survival Game. Another ~Deathworld, although it may have held a powerful civilization before turning grim. A lot of Kapp’s work hasn’t aged well, but this is still a fun read and The Wizard of Anharitte was subversive in its time.

@35: (a truly excellent book published by Baen – I am astonished that James listed it) Why? He’s perfectly capable of seeing a diamond amid the muck.

@46: In one of Hal Clement’s books, we were the only spacefaring species from a world orbiting a star as massive and bright as the Sun, and the only one from a world so hot pure water was liquid. And in another, the only spacefaring species comes from a world so hot even Mercury isn’t warm enough for them, and H20 is something that theory says should exist — but the idea of it covering two-thirds of a planet is … inconceivable.

I suspect that Auberon, in the James S.A. Corey Expanse novella of the same name, is an intentional joke on this trope. Auberon is very pleasant and livable for humans, except that the whole planet smells strongly like crap.

Don’t forget H. Beam Piper’s world of Niflheim! A world with a fluorine atmosphere, geology, and surprisingly, life. Nothing really vigorous, but stuff survives living in what would be a living hell for anyone else.

This is the perfect thread to ask if anyone can help me identify a scifi book I read decades ago and have never read since. All I can remember is that the protagonists had to walk across a new planet for some reason, and as they walked they discovered the atmosphere was infecting them – they were covered in boils or abscesses and then gradually it completely covered each person, and after a couple of days they recovered. Can anyone help?

James Davis Nicoll @46 — In one of Hal Clement’s books, we were the only spacefaring species from a world orbiting a star as massive and bright as the Sun, and the only one from a world so hot pure water was liquid.

Are you thinking of Still River?

@42 IIRC most “habitable” planets in 40k are inhabited by Orcs, which are smarter than Catachan’s wildlife, better armed, reproduce only when they die, and enjoy nothing more than getting together with the Boyz to fight and kill anything that turns up. Catachan is probably safer than most planets. Certainly safer than anything in the Eye of Terror.

@45 Australia was thought quite pleasant by 19th century settlers. About half the people who landed in West Africa, on the other hand, died of some tropical disease within a year, and the death rate in subsequent years was only a little lower. At least for human beings in large numbers, no living thing big enough to see is that dangerous. It is the ones too small to see you have to watch out for. Except you can’t…

Hugh Howey’s Wool and its follow-ups. Also The Aeronaut’s Windlass by Jim Butcher.

@61,

FOUR-DAY PLANET also had its issues.

What was the planet called in The City in the Middle of the Night by Charlie Jane Anders? January. I would not want to live there.

@61: A fluorine atmosphere would be a strong reason to expect life – reactive gases like oxygen and fluorine don’t hang around unless there’s some odd chemistry regenerating them.

Whatever moon it was they tried to terraform in KSR’s “Aurora”. It was a genius of a book basically written on the principle that spaceship Earth is all we’ve got

Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter’s excellent The Long Earth series features travel between alternate earths, essentially in a long chain. Many of the earths are somewhat similar to ours, but some are too hot, some are icy wastelands, and some have dangerous flora and fauna. Uninhabitable planets are called “Jokers;” in one case, the planet is split into pieces; in another, the planet is inhabited mostly by amoebas and similar fauna, some of which is sentient and telepathic.

Speaking of EE Smith: any of the Chloron planets from the Skylark universe

Christopher Anvil’s The Gentle Earth.

Oh, Terra is not a hell planet for humans.

The invading aliens had a different experience.

http://baencd.freedoors.org/Books/The%20World%20Turned%20Upside%20Down/0743498747__25.htm

Tobias Buckell. Sly Mongoose. Tor. 2008. Chilo, a planet featuring ‘corrosive rain, crushing pressure, and deadly heat’, but also cloud cities at 100k ft.

highly recommended.

Earth, per Stephen Baxter’s Flood/Ark duology, and the epilogue short stories, Landfall. Bleak.

Pandora, from Herbert and Ransom’s Destination: Void series. Ugh.

This is a tough one. I feel there should be the distinction between ‘will always die’ and ‘will probably die’. In the ‘will probably die’ category are Dosadi (from “the Dosadi Experiment”) or Loren Two (from ‘Exploration Team”)

(33) Stewart: “Planets humans can attempt to survive on – Finisterre Kesrith, Kutath, Staurn. Worlorn,

Planets humans wouldn’t attempt to survive on – Satan, Mirkheim”

Love CJ!

Didn’t even think of Finisterre at first, don’t want to go there at all!

Bezant 459 from David Drake’s criminally underrated Redliners.

Patra-Baank (Freeze-Bake) from Tony Rothman’s 1978 “The World is Round.” This is my all time favorite Planet of Mystery story. The book never really caught on and is out of print. The planet is giant and rotates very slowly. It has two seasons, day and night. At night the air freezes in some places and during the day rocks melt in some areas. The plot hinges on a quest for metallic hydrogen.

Rothman was a physics grad student when he wrote the book and did a thorough job of calculating the orbital mechanics stuff. He did it on a programmable calculator.

Somebody, hint, ought to reprint this. It has a great story with well developed characters. Its theme is one of my favorites, the interface between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance/Enlightenment.

For a deep cut, how about the Planet of Death by Robert Silverberg.

The unnamed crashed-upon planet in Joanna Russ’s We Who Are About To… is uninhabitable, by dint of the narrator’s sheer determination to make sure of it.

Hey what about some levels of Sursamen?

Some of Rothman’s books are available but not that one. I seem to recall encountering comments from him that indicated the book did OK but he was for some reason unsatisfied with it. Perhaps that’s why it is out of print.

As it happens, my MMPB is just upstairs….

John Dalmas’ series about The Regiment: Oven, Tyss…

Ray Bradbury’s story “The Creatures That Time Forgot” aka “Frost and Fire” features a world where humans landed long before finding that radiation there causes them to live an entire life in 8 days. Luckily they are also born with their ancestors’ memories, making their lives short and unpleasant, but not entirely impossible.

Not printed fiction (though it shows up in some of the canonical spinoff novels, but the place of The Shadows – Z’ha‘dum.)

Not very friendly to humans for several reasons, not just the unbreathable atmosphere.

I would like to remind you all that Pyrrus, Deathworld, was not actually that hostile a place. It became so around the settlement inhabited by Kerk and company because of the way this group interacted with the psionically sensitive environment. If they became less hostile the biosphere would reciprocate. The “grubbers,” the rest of the people on the planet, were able to do this.

How about Heorot from Niven, Barnes and Pournelle’s Legacy of Heorot ?

FYI, another tor article on inhospitable planets: Paradise-not: five inhospitable planets

The world: Ragnarok, The story: Space Prison, The author: Tom Godwin

This is one of my favorite SciFi books, which I first read in the 60’s. A spaceship full of colonists from earth is captured by the alien Gern Empire. The Gerns ruthlessly divide the colonists into two categories – those that are acceptable, those who due to education and ability can be of use to the empire, are kept, and the rejects, those deemed useless to them. The rejects are left on the “habitable ” planet of Ragnarok, half again the gravitation of earth. Disease, and hostile flora and fauna, kills off half of the colonists the first night. This is a multi generational epic that shows that humans are adaptable.

#89, John Kidwell:

The world: Ragnarok, The story: Space Prison, The author: Tom Godwin

The Survivors/Space Prison is my favorite of Goodwin’s stories.

http://baencd.freedoors.org/Books/The%20Cold%20Equations/0743436016___1.htm

@23 I’m minded of a phrase from James Alan Gardner’s ‘Vigilant” about being in a jungle. “Everything wants you dead. Even the things that won’t directly kill you still want you dead. You’re a waste of good nutrients; they want you recycled back into the ecosystem.”

I always thought that Anne Mccaffrey’s Ballybran fit the bill pretty well….Only habitable on the surface for part of the year, with storms that not only devastate it, but send resonances along the crystals that are the sole reason for humans to live on it, so far down that even living deep underground still subjects one to the noise.

Joan D. Vinge’s “Psion” has Cinder, a barely inhabitable world that was once the core of a star. It’s the only one shown in that particular universe that is an inhospitable planet…All the other places she mentions are hellholes due to human activity. Quarro’s undercity being one prime example.

@87 The planet in Niven, Pournelle and Barnes’ Heorot series was actually quite pleasant, except for the biologically supercharged carnivores, that is. I just read the third book, Starborn and Godsons, a nice end to the series.

I went through the list and saw no one had mentioned Leigh Brackett’s Mercury. Eric John Stark, her pseudo-Tarzan hero, grew up in the twilight region (back when they thought Mercury kept one face always to the sun).

Nowadays, we know that it has two days every three years, or is it three days every two years, so it’s not quite tidally locked. Sadly, then, there is no permanent semi-habitable zone at the terminator.

I’m actually proud I managed to resist the urge to make a pun on “Twilight Zone,” or perhaps “Terminator.”

There was also the Niven story (one of the Known Space ones) where the guy was investigating a rogue planet that turned out to be made entirely of antimatter.

“Springworld” from Joe Haldeman’s There is No Darkness (1983) – cowritten with his brother Jack C. Haldeman II.

Heavier gravity than 1 G, ice cold, gale force winds, deadly native fauna. Our hero is a giant among his fellow students in a traveling university set aboard a starship that goes from planet to planet, each with it’s own challenges to face and lessons to teach.

The title is a quote from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.

Asimov wrote a short story where the colonists kept dying of an unknown disease*. The despised smart person figured out it was because the native flora, which seemed edible absorbed beryllium from the environment. Nobody else knew about Be because plot mechanics (Be is useful as it’s strong, light, and stiff — less dense than aluminum, stiffer than steel, transparent to x-rays, etc., so I think it’s very unlikely to be forgotten by a technological society.) and nobody cared that it was concentrated in plants.

* berylliosis. Be is toxic, which is why that non-sparking beryllium-copper wrench costs about as much as a textbook

There was also a Demon class planet in the show VOYAGER, where the rebel holograms wanted to settle, since they didn’t know anybody else who’d actually want the place.

Planet: Abeth

Author: Mark Lawrence

Book: Red Sister

The star is cooling and the planet is covered in glaciers except where the giant space mirror redirects extra light to an ever narrowing equatorial “Corridor”. This is discussed briefly as they’ve lost the technology to reach space, expand the mirror etc, there is no rescue.

The book focuses on the bloody consequences of a slowly growing society confronting ever shrinking resources.